A new international research study has tracked 35,000 commercial fishing and support vessels, identifying their changing of country registration and also identified hotspots of potential unauthorized fishing and activity of foreign owned vessels. Changing the country of origin is a practice also known as “reflagging.”

The study, “Tracking Elusive and Shifting Identities of the Global Fishing Fleet,” was published Jan. 18 in Science Advances, the open access multidisciplinary journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Participants in the project were researchers from Global Fishing Watch, the Maine Geospatial Ecology lab at Duke University and the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

The study found that close to 20% of high seas fishing is done by vessels that are either internationally unregulated or not publicly authorized, with large concentrations of these ships operating in the Southwest Atlantic Ocean and the western Indian Ocean.

Data used in the study is intended to complement the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ Global Record of Fishing Vessels, Refrigerated Transport Vessels and Supply Vessels, a flagship transparency initiative that serves as the official database of information on vessels used for fishing and fishing-related activities.

These resources, plus the International Maritime Organization’s ship identification number scheme, can provide fishery authorities with information needed to adequately monitor vessel activity, implement flag state responsibilities, and inform responsible fisheries management.

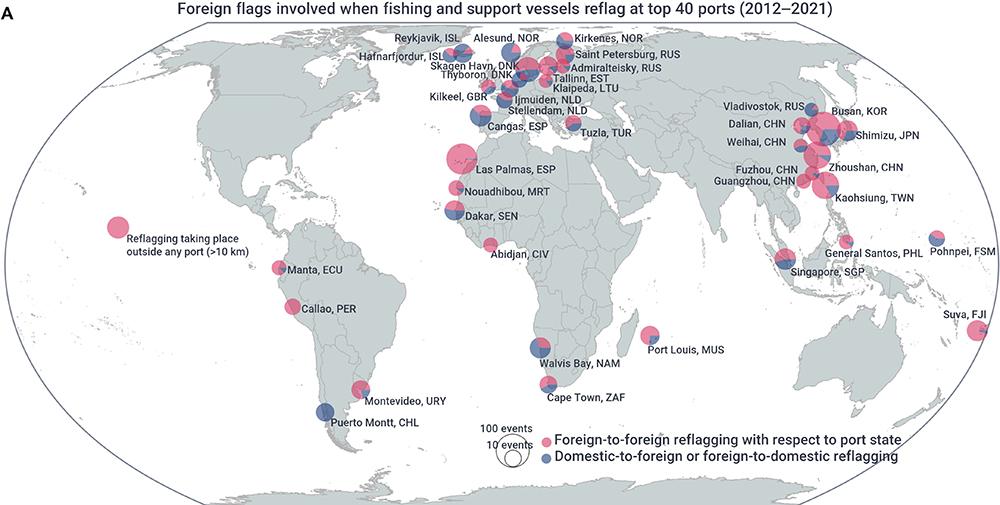

The study found that one-fifth of the 116 states involved in reflagging were responsible for about 80% of this practice over the past decade, with most reflagging happening in Asia, Latin America, Africa and the Pacific Islands, including the ports of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Canary Islands; Busan, South Korea; Zhoushan, China; and Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Most of the reflagging took place in states unrelated to the ports in which they are changing their registrations.

The study notes that while reflagging and foreign ownership are lawful, when not properly regulated and monitored, they can indicate a risk of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. IUU fishing accounts for as much as 20% of the global seafood catch with annual losses valued at up to $23.5 billion.

The study also identified concentrations of fishing activity by foreign-owned vessels, which are focused on parts of the high seas and certain national waters. These include the southwest Pacific, the northwest Indian Ocean, Argentina and the Falkland Islands (Malvinas), and West Africa where vessels are typically owned by China, Chinese Taipei, and Spain.

The hotspots in this study correspond to the areas in which multiple nongovernmental organizations have called for better governance systems.