A new study released Sept. 12 by University of Sydney researchers concludes that the rules for atolls and coral reefs in international law of the sea, already subject to interpretation due to their shifting nature, will be under greater stress as sea levels rise and ocean acidification disrupts reef integrity.

These reef islands, found across the Indo-Pacific are already growing and shrinking due to complex biological and physical processes yet to be fully understood, and now climate change is leading to new uncertainties for legal maritime zones and small island states, according to the study, which was published in Environmental Research Letters.

Thomas Fellowes, a postdoctoral research associate at the university and the lead author of the paper, called the situation “a perfect storm that is bringing instability and uncertainty to what are already difficult boundaries to determine with any great accuracy.”

Fellowes also noted related geopolitical consequences, in that coral reef islands are the legal basis for many large maritime zones.

“Hence the climate disruptions we’re already seeing, and will see in the decades ahead, may have substantial impact not only for small island states, but in hotly contested boundary disputes in places like the South China Sea,” he said.

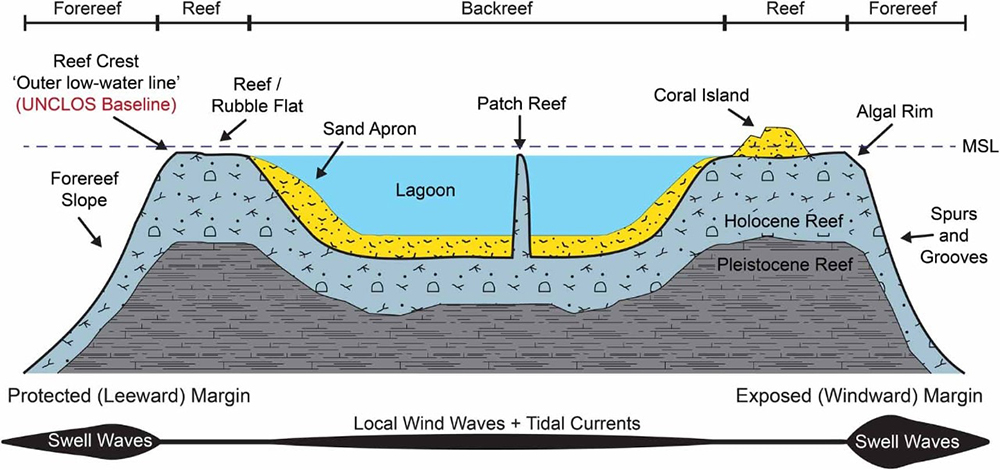

This treaty, signed by 167 nations and almost universally recognized, governs everything from territorial seas, up to 12 nautical miles from a coast or low waterline of a reef to exclusive economic zones of up to 200 nautical miles.

It codifies the rules or freedom of navigation, and allows nations to exploit, conserve and regulate resources in neighboring waters.

The study identifies four ways in which climate change is disrupting coral reef systems in ways that may affect maritime boundaries: sea-level rise, warming oceans, ocean acidification and increased storminess.

Each of these has an impact on the interconnected biophysical processes that allow for creation, retreat and overall structural stability of coral reefs and islands.

The researchers said that one way to buttress existing claims is by defining reef baselines with geographic coordinates like GPS, or remote sensing approaches like satellite bathymetry.

Another way would be to better understand how climate change will affect island habitability, since sustaining human habitation or economic life in a location is another way to establish a viable claim under the treaty, they said.