The commercial fisheries of Hawaii and California may not be quite as active or receive as much media coverage as those in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest, but that doesn’t mean that they are stagnant.

In fact, fisheries in both the Aloha State and Golden State have had plenty of activity over the past year. This article provides a roundup and update of what’s been happening with the Hawaii and California commercial fishing industries over the past several months, and a preview of what could be on the horizon.

Restricted Bottomfish Areas Reopen

On Feb. 25, Hawaii’s Board of Land and Natural Resources (BLNR) approved the re-opening of eight Bottomfish Restricted Fishing Areas (BFRA) that had been closed to fishing since 2007. The re-openings were effective immediately.

The approval followed a similar action from about three years earlier, when four of the 12 total BFRAs were reopened for both commercial and non-commercial fishing of Deep-7 bottomfish species, among Hawaii’s most popular fish for consumption.

In its presentation to the Land and Natural Resources board regarding the reopening, the BLNR’s Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) said it believed that opening all 12 of the BFRAs (four opened as of July 2019), would not adversely affect the overall sustainability of the Main Hawaiian Island Deep-7 fishery and would “be a benefit to local commercial and non-commercial bottom fishers.”

DAR representatives told board members that recently developed annual catch limit-based management, coupled with these rules and strategies, could effectively manage the fishery.

The rules and strategies include stock assessments from the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center; mandatory bottomfish vessel registration; expedited catch reporting; gear restrictions, and commercial size limits.

The main island Deep-7 fishery exists in both state and federal waters, and is managed under a cooperative, joint approach. The state of Hawaii, the NMFS Pacific Islands Regional Office and Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council develop regulations, and the agencies agree on a single set of regulations to make compliance easier.

Marine Monument Ruling

Also in February, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) blocked a proposed rule by the Fishery Management Council to, under certain circumstances, allow the sale of fish caught within the boundaries of Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument.

At its December meeting, the council—which oversees federal fisheries operating in waters offshore of Hawaii, American Samoa, Guam and elsewhere and is commonly known as Wespac—recommended that the NMFS, which is an arm of NOAA, authorize fishing from 50 to 200 nautical miles around the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

To recoup costs associated with fuel, bait and ice, permit holders would have been able to sell, barter or trade their catch. However, in a Feb. 22 letter to Wespac Assistant Administrator Nicole LeBoeuf, NOAA Executive Director Kitty Simonds said that allowing fishermen to sell their catch doesn’t align with the goals and objectives of the proposed sanctuary.

Efforts to designate waters surrounding the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands as a national marine sanctuary began in November 2021.

LeBoeuf said NOAA would begin to develop its own regulations instead but would consider a revised proposal from Wespac. NOAA would consider any revisions until April 14, LeBeouf said.

Commercial Fishermen Collecting Nets

Meanwhile, Hawaii Pacific University’s Center for Marine Debris Research earlier this year launched a project to remove derelict fishing gear from the ocean. A bounty is being paid to eligible commercial fishers to remove derelict fishing gear at-sea before it strikes Hawaii’s coral reefs.

Anglers registered in the bounty project are paid between $1 to $3 per dry pound for derelict fishing gear found at sea and brought back to Oahu, the university confirmed in January.

Hawaii Pacific is partnering with the Hawaii Longline Association (HLA) and DAR on the project, which is partially supported by NOAA’s Marine Debris Program.

The goal, according to the university, is to remove 220,462 pounds (100 metric tons) of derelict fishing gear from the Pacific Ocean over two years.

Such gear is primarily made of plastic and constitutes most of the plastic pollution washing ashore on Hawaii’s beaches.

Before reaching the shoreline, ocean currents tangle up the gear into large masses which as they drift to the shoreline can entangle and drown marine animals, as well as smother and kill the state’s coral reefs.

University staff, students and volunteers are collecting the debris from fishers at the dock and document, measure and weigh it in the net shed. The debris is being repurposed first by local artists, educators and recycling researchers, with the remainder being converted to electricity for Honolulu.

More information on the project, including requirements, registration and safe removal practices, is available on the university’s website: https://tinyurl.com/556xrdrc.

Replacing Blue-Dyed Bait

In late November, Wespac approved a regulatory change recommending replacing blue-dyed fish bait and strategic offal discharge with tori lines as a seabird conservation measure.

The change is based on a fishing-industry-led collaborative project with Hawaii longline vessels conducting field experiments over the past three years to compare seabird interaction rates with baited hooks.

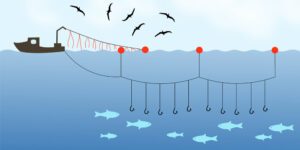

Tori lines consist of a line with streamers and a buoy or extra fishing line attached at the end to create drag. The line is towed from a high point near the stern of the vessel over the area where the baited hooks are deployed.

“The Hawaii Longline Association fully supports this change to tori lines,” HLA Executive Director Eric Kingma said.

Council Executive Director Kitty Simonds added that the action represents “the council’s long history of proactive and adaptive conservation measures to address fishery impacts to protected species.”

Foreign Boat Fishing Licenses

A Hawaii Supreme Court decision released Aug. 11 upheld the local longline fleet’s reliance on foreign fishermen who can’t legally leave the dock when their boats arrive in Honolulu Harbor.

Specifically, the opinion okays state officials granting commercial licenses to fishermen confined to the pier, although they have no legal status in the U.S.

In its decision, the court said that the activity is permissible because the state’s fleet of longline vessels only fish in the deep ocean and not in state-designated waters closer to shore.

The ruling resolved a five-year-old case, “Chun v. Board of Land & Natural Resources,” under which a Hawaiian man, Malama Chun, sued contending that the DLNR couldn’t and shouldn’t issue commercial marine licenses (CMLs) to persons not lawfully admitted to the U.S.

In its ruling, the state Supreme Court disagreed.

“The DLNR is not prohibited from issuing CMLs to foreign nonimmigrant crew members on longline fishing vessels who fish for highly migratory species outside of state waters,” the justices wrote in their decision. “Because the longline fishing vessels at issue here do not fish within state waters, we affirm the circuit court’s order denying Chun’s petition.”

Hawaii’s longline fishing industry consists of about 140 boats that dock in Honolulu Harbor; they fish exclusively for tuna species, marlin, oceanic sharks, sailfish, swordfish and other migratory species.

Federal regulations prohibit longline boats from fishing in specific areas around Hawaii. For example, longline boats can’t fish closer than about 50 miles to the north and east of the main Hawaiian Islands, and 100 miles to their south and west.

Longline fishing is also prohibited in the Exclusive Economic Zone around the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, extending 200 nautical miles seaward.

Global Sustainability Certification

The HLA swordfish, bigeye and yellowfin tuna fishery has achieved certification for sustainable fishing practices, the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) announced in last September.

The certification follows a rigorous 16-month review carried out by third-party assessment group Control Union UK Limited. The fishery is the first from Hawaii to enter the MSC program.

The MSC Fisheries Standard is used globally to assess if a fishery is well-managed and reflects the most up-to-date understanding of internationally accepted fisheries science and management.

The Fisheries Standard has three core principles that every certified fishery must meet, including: 1) sustainable fish stocks, 2) minimizing environmental impact, and 3) effective fisheries management. As well as preserving fish stocks and the marine environment, the MSC certification process ensures that products can be traced to a MSC-certified fishery through required record keeping.

This assessment covers two separate components of the longline fishery carried out by members of the HLA: the Hawaii shallow-set swordfish longline fishery and the Hawaii deep-set tuna longline fishery. The fleet is comprised of 140-plus locally owned vessels. The shallow-set fishery targets swordfish at night, whereas the deep-set fishery targets bigeye tuna during the day.

Shallow-set trips are subject to 100% observer coverage, while a coverage of at least 20% is aimed at for deep-set trips.

The MSC offered congratulations to the association on achieving the milestone.

“The fishery has demonstrated that they’ve put in the hard work to ensure fishing is done in an environmentally sustainable manner, supporting both future generations and our oceans,” MSC U.S. Program Director Nicole Condon said. “As someone who lived in Oahu for several years, I’m thrilled to personally welcome the first fishery from Hawaii into the program.”

“HLA is proud to receive the certification as it is recognition of the fleet’s stringent management and monitoring regime,” Kingma said. “We believe our fleet produces the best quality and highest level of monitored tuna in the world. We look forward to working with MSC, (Westpac), NMFS and others on the continued and long-term production of sustainably and responsibly harvested fish landed by our fleet.”

The Hawaii longline fishery dates to 1917, when it was established by Japanese immigrants. Today, it’s the largest food-producing industry in Hawaii, with unique importance in a state whose residents consume twice as much seafood per capita as the rest of the country.

The fishery is low volume and high value, with landings worth about $125 million annually. This makes Honolulu one of the nation’s most valuable commercial fishing ports year after year; 80% of landings are consumed locally in Hawaii, and nearly 100% stay within the U.S.

Overall, the fishery produces 95% of the nation’s bigeye tuna landings and 50 to 60% of swordfish and yellowfin tuna landings, according to the HLA.

An important component of the fishery is the Honolulu Fish Auction, which is the only daily tuna auction in the U.S. The auction, which is celebrating its 70th year in business in 2022, plays a key role in promoting the best quality and highest market value of fish landed by the Hawaii longline fleet.

California Hatchery Chinook Projection

The Feather River Fish Hatchery in the Northern California city of Oroville is expected to increase production of fall-run Chinook salmon in 2023 to some 9.5 million fish to combat impacts of drought and a thiamine deficiency affecting natural spawning and in-river production.

The plan, announced in December by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) and the California Department of Water Resources (DWR), marks the second consecutive year that the Feather River Fish Hatchery is expected to exceed its typical production quota of six million fall-run Chinook salmon to help sustain the state’s commercial and recreational salmon fisheries.

In 2022, the hatchery raised and released eight million fall-run Chinook salmon smolts. The hatchery, owned by DWR and operated by CDFW, is seeking to produce some eight million fall-run Chinook salmon smolts and 1.5 million fall-run Chinook salmon fingerlings in 2023—a 3.5 million fish increase over typical production goals.

CDFW Fisheries Branch Chief Jay Rowan said that given the prolonged drought, low adult returns and a thiamine deficiency impacting in-river production, his agency feels it is extremely important to maximize the actions available to them in hatcheries to help sustain this extremely important salmon population.

The Feather River Fish Hatchery has collected 17 million fall-run Chinook salmon eggs to help meet these production goals—two million more eggs than the hatchery’s typical egg collection target, according to the CDFW.

Some 11,000 adult fall-run Chinooks returned to the hatchery in 2022, a significant, below-average return. Two million of the additional salmon smolts produced are to be trucked to release sites in the San Pablo and San Francisco bays to maximize survival.

Another 1.5 million of these additional fish are to be released into the Feather River earlier in the season and at a smaller size than typical river releases.

CDFW officials said this is an experimental effort to take advantage of more favorable weather and river conditions in early spring, and that 25% of the fall-run Chinook salmon produced by the Feather River Fish Hatchery in 2023 is expected to be marked and tagged so that scientists can monitor the releases’ success.

Oil Spill Settlement

On Feb. 9, multiple shipping companies agreed to pay a total of $45 million to people and businesses that suffered due to the 25,000-gallon oil pipeline leak offshore of the Orange County city of Huntington Beach in Southern California in October 2021.

The spill forced a fisheries closure from Huntington Beach to Dana Point in Orange County on Oct. 3. The closure, implemented by the CDFW, prohibited the take of all fish and shellfish in that area.

The state’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment determined at the time that a threat to public health was likely from consuming fish in the affected area. In the following days, the original closure area was expanded to include 650 square miles of marine waters and about 45 miles of shoreline, including all bays and harbors from Seal Beach to San Onofre State Beach.

On Nov. 30, the closure order was lifted after the office declared that there was no further risk to public health from seafood consumption in the affected area and recommended that fishing and consumption of seafood from the area resume.

The settlement, combined with an Amply Energy settlement in 2022, provides a total of nearly $100 million to class members whose businesses and property were harmed by the spill, including commercial fishers.

“It sends a clear message to large corporations operating off the coast of California that they will be held responsible for their negligence,” the class members’ legal counsel Wylie Aitkin, Lexi Hazam and Stephen Larson said in a statement.

As a result of the allegedly negligent conduct, an estimated 25,000 gallons of crude oil were discharged from a point about 4.7 miles offshore of Huntington Beach from a crack in the 16-inch pipeline.

The shipping companies involved in the settlement have denied the class members’ allegations, but pipeline owner Amplify Energy settled with the class members in October 2022 for $50 million.

Members of the class action suit alleged that container ships repeatedly crossed over and struck the Amplify Energy pipeline with their anchors on Jan. 25, 2021, during heavy weather.

The container ships’ anchor strikes, the class members claimed, displaced the pipeline and damaged its concrete casing, leading to the pipeline’s failure nine months later.

Alaska Bureau Chief Margaret Bauman contributed to this report.