Wild salmon in Western Alaska are engaged in constant battle with land and ocean heat waves, among other challenges, resulting in fewer fish returning to the Yukon River, according to the annual Arctic Report Card, a collaborative effort of NOAA Fisheries and other stakeholders.

The NOAA Fisheries 2023 Ecosystem Status Reports for Alaska, released by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) on Dec. 15, contains special sections on salmon, which note that in 2022, 81% fewer king salmon returned than average to the Yukon River, a new record low and part of a long-term decline seen across Alaska.

The report also notes that the cause of the decline is complex and that researchers have found possible links to water temperature, disease and declining size of the fish.

The Arctic has been an area of particular focus for researchers because the region is disproportionately impacted by climate change. The report, released during the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco, covered a wide range of topics, including oceans, weather and fisheries research.

“There is still a lot we don’t know,” Rick Thoman, the lead editor and a climate specialist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy, said. “But it seems clear … that climate-induced changes look like bigger factors than the bycatch. Warmer on-land conditions and in the ocean are changing the food supply and predators (for fish). It appears that these environmental issues are playing a larger role.”

Thoman said he’s optimistic that Alaskans will adapt to these changes, because they have no choice. “It seems perfectly clear at this point that we are going to do things differently than in the past, but it is going to be a different Alaska than what we are used to,” he remarked.

“We’ve seen heatwaves in the ocean and heatwaves on land, and salmon populations have been responding with extreme ups and downs,” Erik Schoen, lead author of the salmon chapter and a fisheries scientist at the UAF International Arctic Research Center, said.

Peter Westley, a scientist at the UAF College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, was also among the salmon chapter co-authors.

“We know that king populations on the Yukon do worse when the adult salmon swimming upriver to spawn experience high river temperatures and low flow, which tend to be correlated with hot, dry years,” Schoen explained. “There’s also a disease called Ichthyophonus that can interfere with a salmon’s ability to swim.”

In 2022, observers in the research network found that more frequent and intense coastal storms contributed to flooding in communities and coastline erosion. Shifting wind patterns altered the sea ice, improving access to marine mammal hunting areas.

Chum salmon were also facing challenges. In 2021, 92% fewer adults returned to the Yukon River than average, and until then chum populations had been stable.

Image via NOAA Fisheries.

The report notes that the decline has been linked to unprecedented heatwaves and loss of sea ice in the Bering Sea, and that juvenile chum salmon ate lower quality food and put on less fat under those conditions, potentially reducing their survival rates.

“One thing that is very important to appreciate is that slowing climate change is a very sluggish process,” said Daniel Schindler, a professor at the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, whose research focuses on causes and consequences of ecosystem dynamics.

Of particular interest to him are the effects of changing climate on trophic interactions and services provided by aquatic ecosystems.

“Even if we could drastically reduce greenhouse gas emission at the snap of our fingers, we will be living in a warmer future for most of the next century,” Schindler remarked. “Most of the human-caused change to our climate system has been to heat up the oceans which will take a very long time (on the order of several decades) to cool off.”

“The other reality is that there are things we can do to manage climate ‘impacts’ on ecosystems right now,” he added. “In fisheries, I think we can do several things to give fishes a good chance of coping with climate change. This includes actions like protecting and restoring habitat, having harvest policies that are responsive to changes in the productivity of fish populations, effectively monitoring fish populations to keep our finger on the pulse so that harvest rates can be adjusted accordingly (and) reducing additional stresses on populations like pollutants.”

Schindler, like Thoman, said he is, all things considered, optimistic.

“We have to be,” he told Fishermen’s News. “I think we need to separate the long-term needs from the short-term needs. The progress made at the global level via COP28 (United Nations Climate Change Conference) meetings etc., is pretty dismal.”

“We might get to a point where we can reverse global trends in emissions but this is taking a very long time to play out,” he said. “But we can’t wait for the global strategy to fall into place before we do tangible work at local and regional scales to reduce climate impacts.”

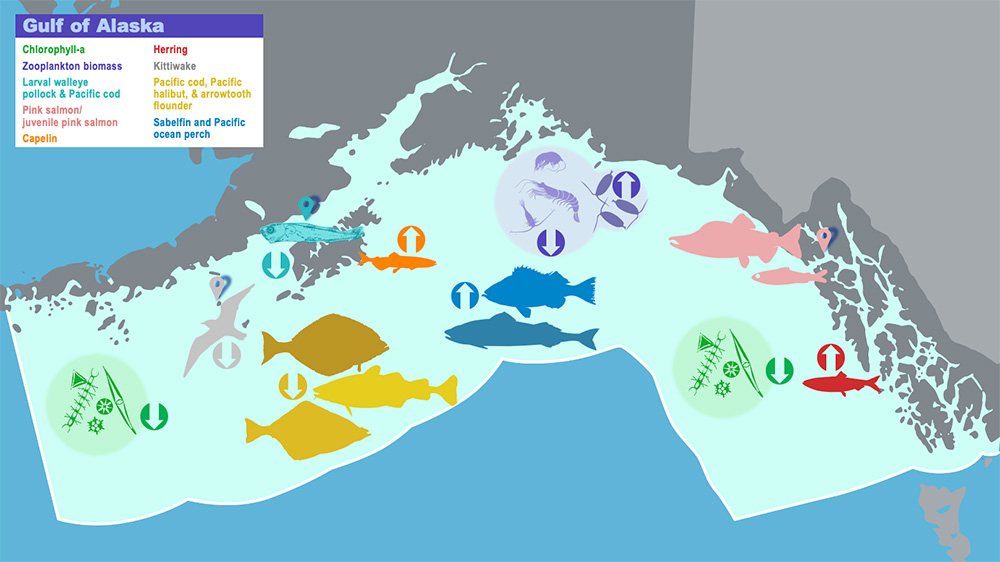

The annual report also included ecosystem updates for the eastern Bering Sea, Aleutian Islands and Gulf of Alaska. It describes current conditions and trends over time for key oceanographic, biological and ecological indicators in the three Alaska marine ecosystems.

“Warming at rates four times faster than the rest of the ocean, Alaska’s Arctic ecosystems are a bellwether for climate change,” Robert Foy, director of the Alaska Fisheries Science Center, near Juneau, said. “Now more than ever having ecosystem and climate-related data and information is essential to support adaptive resource management and resilient commercial, recreational and subsistence fisheries, and rural and coastal communities.”

Highlights of the report include several notable indicators:

- Ocean temperatures in the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea have cooled relative to recent marine heatwave conditions, while the Aleutians remained warmer than average this year.

- Pacific Ocean perch continue to be the dominant groundfish in the Aleutians, replacing pollock and Atka mackerel in the ecosystem. The Gulf of Alaska ecosystem by comparison is now characterized by increases numbers of Pacific Ocean perch and sablefish, with reduced numbers of Pacific cod, Pacific halibut and arrowtooth flounder.

There are positive signs for Pacific cod recruitment in the Gulf of Alaska, although adult numbers of Pacific cod remain low.

There are notable indicators of ecosystem health and potential threats to wildlife and human health. Harmful algal blooms are becoming more prevalent in the northern Bering Sea and paralytic shellfish toxins in sampled blue mussels from four Aleutian Island communities were 47 times above the regulatory limit.

Links to detailed reports on the Gulf of Alaska, Aleutians and Eastern Bering Sea can be found online at http://tinyurl.com/5n68hvrd.